What is Liturgy?

The term Liturgy did not appear until the 16th century from biblical scholars.

CCC 1069 The word “liturgy” originally meant a “public work” or a “service in the name of/on behalf of the people.” In Christian tradition, it means the participation of the People of God in “the work of God.” Through the liturgy Christ, our redeemer and high priest, continues the work of our redemption in, with, and through his Church.

Christian participation in “Opus Dei” (the work of God)

How do we relate to God in worship and liturgy? There are 3 modes:

Autonomy Participatory Theonomy Hegemony

(self-rule) (God-rule) (Tyrannical rule)

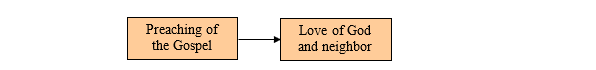

God wants us to participate in his Trinitarian nature. We are to “participate” in liturgical worship.

2 Pt 1:4 that through these [promises] you may escape from the corruption that is in the world because of passion and become partakers of the divine nature

Pope Pius XII said “in the Liturgy you should see the Priesthood of Christ and His sacerdotal (priestly) ministry.” Pope Pius XII draws our attention to Christ and our participation in the mystical Body of Christ (Church) rather than what we do or derive from it.

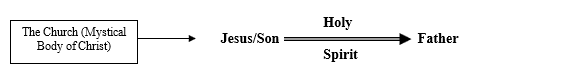

The eternal praise of the Father by the Son takes place through the Holy Spirit and we participate in this eternal praise by virtue of being the Mystical Body of Christ – the Church.

Christ, in His Church, incorporates us into something He is doing for eternity, therefore we are to participate.

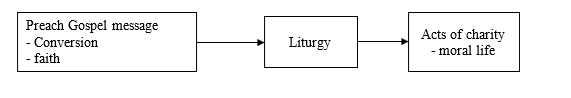

Liturgy as Source of Life

CCC 1071 As the work of Christ, liturgy is also an action of his Church.

It makes the Church present and manifests her as the visible sign of the communion in Christ between God and men. It engages the faithful in the new life of the community and involves the “conscious, active, and fruitful participation” of everyone.

What is considered Liturgical?

Mass – summit of liturgical (Christian) life

Liturgy of the Hours – sanctification of the day.

Sacraments – sanctification of stages in life.

Sacramentals – elevate common occasions in life. (i.e. grace before meals – we elevate it to an occasion for holiness.)

The liturgy is the highest activity engaged by the Church and is “the font of from which all her power flows,” but it isn’t the only activity in the Church. (CCC 1074)

How are We to Worship?

The Bible was the Church’s first liturgical book, but the Bible did not exist in its present form (New Testament) nor did it have rubrics (the steps describing exactly what to do and say).

Note: the word “rubric” comes from the Latin word meaning “red” for the red letters in the liturgical books.

Two Liturgical Families or Rites:

- Western or Latin Liturgical Family

- Roman

- Ambrosian (Milan)

- Mozaranic (Toledo Spain)

- Cistercian, Carmilite, Dominican…(various religious orders)

- Eastern Liturgical Family

- Constantinople Family – Byzantine (E. Europe, Russia)

- Jerusalem Family

- Alexandrian Family (North Africa) – Coptic, Ethiopian

- Antiochene Family

- Cappadocian Family – Armenian, Byzantine

Liturgy In the Ancient Church

Jesus did not lay down in detail how the worship was to be done. He left that up to the Church.

- The first Christian Liturgy was held in the evening on Saturday

- Start at sundown and continue to midnight.

- Food and wine was shared among the faithful as a symbol of mutual charity (loveLove To put the needs of another before our own. To will the good of the other.). This was known as the Agape (love) meal.

- There were sermons or talks. (Acts 20:9)

- Over time, the food and wine portion faded because it became unruly. (1 Cor 11:20)

Rich began holding back their good food and the rich would eat better than the poor.

- They were lasting longer than midnight and communion was being pushed off to dawn to let people get sober because of the abuse.

- By the 4th century the agape meal has disappeared.

- Prayer in the Synagogue (daily in the morning)

- Singing of hymns, reading of the Law, Psalms, reading of the prophets and finally a sermon (Jesus read Isaiah and then made a commentary – Lk 4:15ff)

- “And they devoted themselves to the apostlesapostles In Christian theology, the apostles were Jesus’ closest followers and primary disciples, and were responsible for spreading his teachings.’ teaching and fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers . . . And day by day, attending the temple together and breaking bread in their homes, they partook of food with glad and generous hearts“ (Acts 2:42, 46)

- When Synagogue prayer ended because of persecution, the Christians were kicked out of the synagogue and the Saturday (Sabbath) night portion (agape prayer) was moved to the morning on Sunday.

- Singing of hymns

- Reading of the Law (Old Testament)

- Psalms

- “New Testament” reading (memorial of the apostles)

- Reading of the prophets

- Sermon (Homily)

- Communion (agape meal)

By about the 2nd century the two parts of the Mass came together. The reading of scriptures came first then the agape meal.

The Liturgy in the 1st through the 3rd century

- The liturgical year – centered on Easter (no Advent, Pentecost, etc.) Every Sunday was a “little” Easter.

- No temporal cycle – no unfolding of the mysteries of Christ throughout the year through a liturgical calendar (e.g. Advent, Christmas, Lent, etc).

- Nor sanctoral cycle – meaning no cycle of saints or saint feast days.

- Church is charismatic – no fixed formulas or rubrics (except for the consecration).

- Early church fathers saw the liturgy as a sign of Catholicity (universality). One is participating in the work of God. Other pagan religions had long sets of prayers, unlike the Christians, but the Holy Spirit was speaking through the Church and all were saying the “same” thing – same message is being preached. Spontaneous spirit-based praying was a sign of Catholicity.

- Liturgy was in Greek, which was the common language. It facilitated participation. Latin later became the common (vulgate) language.

St. Justin Martyr (150 AD)

St. Justin Martyr describes the liturgy:

First mention of the “sign of peace” (a kiss) in the liturgy

Most of the prayers are directed to the Father.

Eucharistic discourse was made longer.

The people say Amen to certain prayers

Have what we know as communion (Eucharist) today.

Read memoirs of the apostles (Gospels) as long as time allows.

Having ended the prayers, we salute one another with a kiss. There is then brought to the president of the brethren bread and a cup of wine mixed with water; and he taking them, gives praise and glory to the Father of the universe, through the name of the Son and of the Holy Ghost, and offers thanks at considerable length for our being counted worthy to receive these things at His hands. And when he has concluded the prayers and thanksgivings, all the people present express their assent by saying Amen[1]

St. Hippolytus 3rd Century

Dialogic structure is evident. People making replies to the prayers became more extensive.

- “Peace be with you.” . . . “And with your spirit”

Edict of Milan (313 AD)

Emperor Constantine declared the Christian faith to no longer be outlawed. He made it the official faith of Rome.

Pilgrimages are made to the shrines of early Christians and Mass is celebrated there.

The Liturgy in the 4th through the 7th Century

- Switch to Latin in 4th century was beginning and evolved naturally.

- Move toward fixed text of reading and prayers (no rubrics, yet)

- Temporal cycle is growing (feasts of the Lord in relation to salvation history)

- Sanctoral cycle is growing (Saint feast days)

- Non-essential rites begin to appear in the liturgy. (e.g. ordination of a priest)

- Councils begin to make contributions to liturgical formulas.

– “our lord Jesus Christ who lives and reigns with the father and Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever.”

- High laity participation.

– frequent Amens and dialogues

The Liturgy in the 8th through the 12th century

- Mass stays in Latin but is not the commonly spoken language. Latin is the language of science and education. Preserved as a liturgical language. Using one language provides theological accuracy.

- Sharp decline in the number of liturgical text produced and a rise in texts being re-edited or collected. Not drafting new liturgical prayers – copying and distributing.

- Rise in rubrics and use of liturgical books. (red writing explained the action)

- Temporal and sanctoral cycles were well in place.

- Great drop in lay participation (not a drop in attendance).

– Arianism denied the divinity of Christ. Then Church over emphasized the deity of Christ. People saw Jesus as unapproachable and less people received the Eucharist. This was an over-reaction to Arianism.

– Prayers reflect the primacy and even exclusivity of the action of the priest. The laity is less inclined to push their participation.

– Rise of the silent canon because people didn’t know Latin. The Eucharist was unapproachable and gave rise to priest exclusivity.

– Logical conclusion is the rise of private devotion.

- If you were just an observer at this time, you would recognize it as a Mass of today. But you would not participate in it.

The Liturgy in the 13th through the 15th century

- Liturgical texts are set. (e.g. Breviary = Liturgy of the hours or the Divine Office is also set.)

- Exact performance was required (strict adherence).

The Liturgy in the 16th Century – Council of Trent and liturgy

- The Council of Trent ran out of time and handed the liturgical reform over to Pope Pius V. He centralized authority in the Congregation of Rites. This mass is what we know today as the Tridentine Mass.

- All liturgies not older that 200 years had to conform to this new liturgy. Those other older liturgies could be retained.

- Much higher degree of uniformity in liturgical practice.

- Trent gave us an educational system for priests (seminary)

- Very few things were going wrong at Mass now. Liturgical books were edited in Rome to keep them in check.

- Disadvantages: People were going to Mass but not receiving communion, because of their fear of receiving God. Emphasis is on externals (actions) instead of internals (spiritual).

The Liturgy in the 17th to 19th Century

After 300 years of this, one is going to absorb certain aspects of the liturgy, but these are not necessary for the benefit of the Liturgy. The sense of why Trent did what they did was lost.

- Sanctoral cycle was out of control

- Truly the age of Rubricists. (not explaining why certain things were done – e.g. kissing the altar, because it represents Christ – our bridge to God, the rock which Moses struck, Jesus is the foundation stone, etc.) They did it because they wanted certainty that the action was going to take effect. Strict adherence to rubrics.

The Liturgy in the 20th Century

The Liturgical Movement

Pope St. Pius X (1903-1914)

- Lowered the age of first communion reception and encouraged frequent communion.

- Pruned back the sanctoral cycle.

- 1903 used the term “active participation of the laity.”

Pope Pius XII (1950’s)

- Lots of discussion regarding reform to the liturgy. Pope Pius XII stepped in as a “referee” in the liturgical movement.

- Sept 3, 1958 was first time in over 1000 years that the laity were allowed to say the Our Father at Mass.

- Restored holy week (Triduum) – Holy Thursday and Good Friday.

Missal of Paul VI – Missal of 1969

Vatican II determined that the liturgy needed to be updated for “the times.”

Post Vatican Council II

- Increase in the number of Eucharistic prayers

- Homily restored as a requirement in Sunday masses

- Prayer of faithful restored (the “intentions”)

- Cycle of readings is 3 years – A third reading is added (now the first reading of the OT).

- Restored the Responsorial Psalm. It was not a regular portion of the Tridentine Mass.

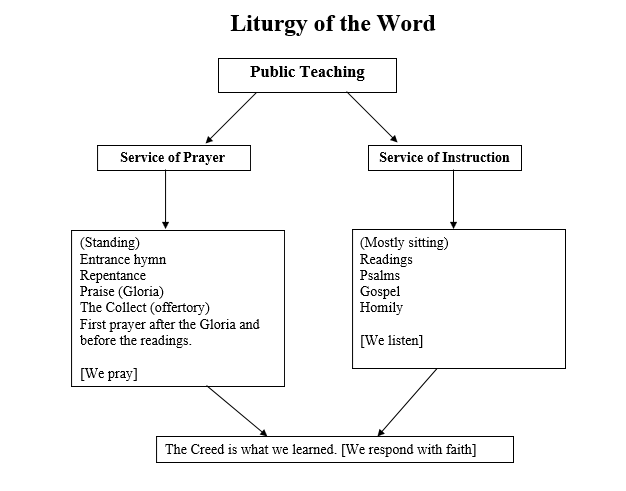

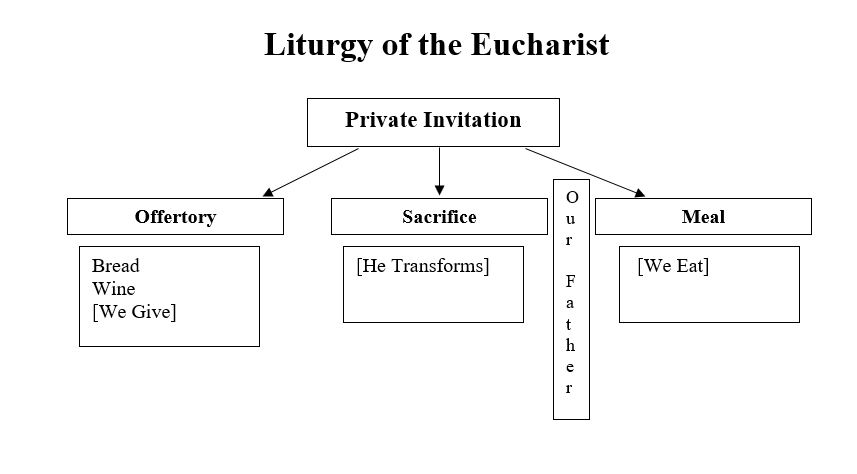

The Structure of the Mass

Liturgy of the Word and Liturgy of the Eucharist

[1] Justin Martyr, “The First Apology of Justin,” in The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus, ed. Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, vol. 1, The Ante-Nicene Fathers (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1885), 185.