Doctor of the Church (Latin: doctor “teacher”), also referred to as Doctor of the Universal Church (Latin: Doctor Ecclesiae Universalis), is a title given by the Catholic Church to saints recognized as having made a significant contribution to theology or doctrine through their research, study, or writing.[1]

As of 2024, the Catholic Church has named 37 Doctors of the Church. Of these, the 18 who died before the Great Schism of 1054 are also held in high esteem by the Eastern Orthodox Church, although it does not use the formal title Doctor of the Church.

Among the 37 recognized Doctors, 28 are from the West and nine from the East; four are women and thirty-three are men; one is an abbess, three are nuns, and one is a tertiary associated with a religious order; two are popes, 19 are bishops, twelve are priests, and one is a deacon; and 27 are from Europe, three are from Africa, and seven are from Asia. More Doctors (twelve) lived in the fourth century than any other; eminent Christian writers of the first, second, and third centuries are usually referred to as the Ante-Nicene Fathers. The shortest period between death and nomination was that of Alphonsus Liguori, who died in 1787 and was named a Doctor in 1871 – a period of 84 years; the longest was that of Irenaeus, which took more than eighteen centuries.

Before the 16th century

In the Western church four outstanding “Fathers of the Church” attained this honour in the early Middle Ages: Gregory the Great, Ambrose, Augustine of Hippo, and Jerome. The “four Doctors” became a commonplace notion among scholastic theologians, and a decree of Boniface VIII (1298) ordering their feasts to be kept as doubles throughout the Latin Church is contained in his sixth book of Decretals (cap. “Gloriosus”, de relique. et vener. sanctorum, in Sexto, III, 22).[2]

In the Byzantine Church, three Doctors were pre-eminent: John Chrysostom, Basil the Great, and Gregory of Nazianzus. The feasts of these three saints were made obligatory throughout the Eastern Empire by Leo VI the Wise. A common feast was later instituted in their honour on 30 January, called “the feast of the three Hierarchs“. In the Menaea for that day it is related that the three Doctors appeared in a dream to John Mauropous, Bishop of Euchaita, and commanded him to institute a festival in their honour, in order to put a stop to the rivalries of their votaries and panegyrists.[2]

This was under Alexius Comnenus (1081–1118; see “Acta SS.”, 14 June, under St. Basil, c. xxxviii). But sermons for the feast are attributed in manuscripts to Cosmas Vestitor, who flourished in the tenth century. The three are as common in Eastern art as the four are in Western. Durandus (i, 3) remarks that Doctors should be represented with books in their hands. In the West analogy led to the veneration of four Eastern Doctors, Athanasius of Alexandria being added to the three hierarchs.[2]

Latin Church

In the Latin Church, the four Latin Doctors (Ambrose, Augustine, Jerome, and Gregory) had been given a special pre-eminence since the eighth century, but in 1298 Pope Boniface VIII declared them Doctors of the Church.[3] Pope Pius V recognized the four Great Doctors of the Eastern Church (John Chrysostom, Basil the Great, Gregory of Nazianzus, and Athanasius of Alexandria) in 1568.[4]

To these names others have subsequently been added. The requisite conditions are enumerated as three: eminens doctrina, insignis vitae sanctitas, Ecclesiae declaratio (i.e. eminent learning, a high degree of sanctity, and proclamation by the church). Benedict XIV explains the third as a declaration by the supreme pontiff or by a general council.[2]

The decree is issued by the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints and approved by the pope, after a careful examination, if necessary, of the saint’s writings. It is not in any way an ex cathedra decision, nor does it even amount to a declaration that no error is to be found in the teaching of the Doctor. It is, indeed, well known that the very greatest of them are not wholly immune from error. Previously, no martyrs were on the list, since the Office and the Mass had been for Confessors. Hence, as Benedict XIV pointed out during his pontificate, Ignatius of Antioch, Irenaeus of Lyons, and Cyprian of Carthage were not called Doctors of the Church.[2] This changed in 2022 when Pope Francis declared Irenaeus of Lyons the first martyred Doctor.

The Doctors’ works vary greatly in subject and form. Augustine of Hippo was one of the most prolific writers in Christian antiquity and wrote in almost every genre. Some, such as Pope Gregory the Great and Ambrose of Milan, were prominent writers of letters. Pope Leo the Great, Pope Gregory the Great, Peter Chrysologus, Bernard of Clairvaux, Anthony of Padua and Lawrence of Brindisi left many homilies. Catherine of Siena, Teresa of Ávila, John of the Cross and Therese of Lisieux wrote works of mystical theology. Athanasius of Alexandria and Robert Bellarmine defended the church against heresy. Bede the Venerable wrote biblical commentaries and theological treatises. Systematic theologians include the Scholastic philosophers Anselm of Canterbury, Albert the Great, and Thomas Aquinas.

In the 1920 encyclical Spiritus Paraclitus, Pope Benedict XV refers to Jerome as the church’s “Greatest Doctor”.[5]

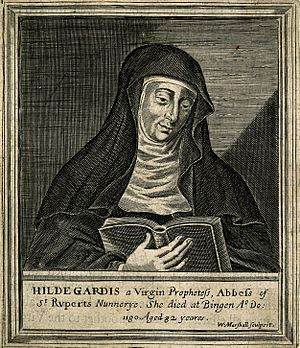

Until 1970, no woman had been named a Doctor of the Church. Since then four additions to the list have been women: Teresa of Ávila (also known as Saint Teresa of Jesus) and Catherine of Siena by Pope Paul VI; Therese of Lisieux[6] by Pope John Paul II; and Hildegard of Bingen by Benedict XVI. Teresa and Thérèse were both Discalced Carmelites, Catherine was a Dominican, and Hildegard was a Benedictine nun.

Traditionally, in the Liturgy, the Office of Doctors was distinguished from that of Confessors by two changes: the Gospel reading Vos estis sal terrae (“You are the salt of the earth”), Matthew 5:13–19, and the eighth Respond at Matins, from Ecclesiasticus 15:5, In medio Ecclesiae aperuit os ejus, * Et implevit eum Deus spiritu sapientiae et intellectus. * Jucunditatem et exsultationem thesaurizavit super eum. (“In the midst of the Church he opened his mouth, * And God filled him with the spirit of wisdom and understanding. * He heaped upon him a treasure of joy and gladness.”) The Nicene Creed was also recited at Mass, which is normally not said except on Sundays and the highest-ranking feast days. The 1962 revisions to the Missal dropped the Creed from feasts of Doctors and abolished the title and the Common of Confessors, instituting a distinct Common of Doctors.[citation needed]

On 20 August 2011, Pope Benedict XVI announced that he would soon declare John of Ávila a Doctor of the Church.[7] It was also reported in December 2011 that Pope Benedict intended to declare Hildegard of Bingen as a Doctor of the Church, though she had not yet been canonized.[8] Pope Benedict XVI declared Hildegard of Bingen a saint on 10 May 2012, clearing the way for her to be named a Doctor of the Church,[9] then declared both John of Ávila and Hildegard of Bingen Doctors of the Church on 7 October 2012.[10]

Pope Francis declared the 10th-century Armenian monk Gregory of Narek the 36th Doctor of the Church on 21 February 2015.[11] The decision was somewhat controversial, as Gregory was a monk of the Armenian Apostolic Church, a non-Chalcedonian church that was not in communion with the Catholic Church during Gregory’s life and has sometimes been described as monophysite. However, the Armenian Apostolic Church does not accept monophysitism, and in 1996, Pope John Paul II and Catholicos Karekin I, patriarch of the Armenian Apostolic Church, signed a joint declaration which said that the division between the two churches was due to historical misunderstandings, not a real difference in Christology. Further, Gregory had been recognized as a saint by the Catholic Church since it received the Armenian Catholic Church into full communion.[12]

List of Doctors

(For earlier authorities on Christian doctrine, see Church Fathers and Ante-Nicene Fathers) * indicates a saint who is also held in high esteem by the Eastern Orthodox Church.

| No. | Name | Titles | Born | Died | Promoted | Activity | Notable writings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Gregory the Great* | One of the four Great Latin Fathers | 540 (c.) | 604 | 1298 | Pope, OSB | Dialogues, Libellus responsionum, Pastoral Care, Moralia in Job |

| 2. | Ambrose* | One of the four Great Latin Fathers | 340 (c.) | 397 | 1298 | Bishop of Milan | Ambrosian hymns, Exameron, De obitu Theodosii |

| 3. | Augustine of Hippo* | One of the four Great Latin Fathers; Doctor gratiae (Doctor of Grace) | 354 | 430 | 1298 | Bishop of Hippo (now Annaba) | De doctrina Christiana, Confessions, The City of God, On the Trinity |

| 4. | Jerome* | One of the four Great Latin Fathers | 347 (c.) | 420 | 1298 | Priest, monk | Vulgate, De Viris Illustribus |

| 5. | Thomas Aquinas | Doctor angelicus (Angelic Doctor); Doctor communis (Common Doctor) | 1225 | 1274 | 1567 | Priest, Theologian, OP | Summa Theologiae, Summa contra Gentiles |

| 6. | John Chrysostom* | One of the four Great Greek Fathers | 347 | 407 | 1568 | Archbishop of Constantinople | Paschal Homily, Adversus Judaeos |

| 7. | Basil the Great* | One of the four Great Greek Fathers | 330 | 379 | 1568 | Bishop of Caesarea | Address to Young Men on Greek Literature, On the Holy Spirit |

| 8. | Gregory of Nazianzus* | One of the four Great Greek Fathers | 329 | 389 | 1568 | Archbishop of Constantinople | On God and Christ: The Five Theological Orations and Two Letters to Cledonius |

| 9. | Athanasius* | One of the four Great Greek Fathers | 298 | 373 | 1568 | Archbishop of Alexandria | On the Incarnation, The Life of Antony, Letters to Serapion |

| 10. | Bonaventure | Doctor seraphicus (Seraphic Doctor) | 1221 | 1274 | 1588 | Cardinal Bishop of Albano, Theologian, Minister General, OFM | Commentary on the Sentences of Lombard, The Mind’s Road to God, Collationes in Hexaemeron |

| 11. | Anselm of Canterbury | Doctor magnificus (Magnificent Doctor); Doctor Marianus (Marian Doctor) | 1033 or 1034 | 1109 | 1720 | Archbishop of Canterbury, OSB | Proslogion, Cur Deus Homo |

| 12. | Isidore of Seville* | 560 | 636 | 1722 | Archbishop of Seville | Etymologiae, On the Catholic Faith against the Jews | |

| 13. | Peter Chrysologus* | 406 | 450 | 1729 | Bishop of Ravenna | Homilies | |

| 14. | Leo the Great*[13] | Doctor unitatis Ecclesiae (Doctor of the Church’s Unity) | 400 | 461 | 1754 | Pope | Leo’s Tome |

| 15. | Peter Damian | 1007 | 1072 | 1828 | Cardinal Bishop of Ostia, monk, OSB | De Divina Omnipotentia, Liber Gomorrhianus | |

| 16. | Bernard of Clairvaux | Doctor mellifluus (Mellifluous Doctor) | 1090 | 1153 | 1830 | Priest, OCist | Sermones super Cantica Canticorum, Apologia ad Guillelmum, Liber ad milites templi de laude novae militiae |

| 17. | Hilary of Poitiers* | Doctor divinitatem Christi (Doctor of the Divinity of Christ) | 300 | 367 | 1851 | Bishop of Poitiers | Commentarius in Evangelium Matthaei |

| 18. | Alphonsus Liguori | Doctor zelantissimus (Most Zealous Doctor) | 1696 | 1787 | 1871 | Bishop of Sant’Agata de’ Goti, CSsR (Founder) | The Glories of Mary,Dogmatic Works: Moral Theology, The Council of Trent, The Histories of Heresies and their Refutation, Truth of the Faith |

| 19. | Francis de Sales | Doctor caritatis (Doctor of Charity) | 1567 | 1622 | 1877 | Bishop of Geneva, CO | Introduction to the Devout Life, Letters of Spiritual Direction |

| 20. | Cyril of Alexandria* | Doctor Incarnationis (Doctor of the Incarnation) | 376 | 444 | 1883 | Archbishop of Alexandria | Commentaries on the Old Testament, Thesaurus, Discourse Against Arians, Dialogues on the Trinity |

| 21. | Cyril of Jerusalem* | 315 | 386 | 1883 | Archbishop of Jerusalem | Catechetical Lectures, Summa doctrinae christianae | |

| 22. | John Damascene* | 676 | 749 | 1890 | Priest, monk | Fountain of Knowledge, Octoechos | |

| 23. | Bede the Venerable* | Anglorum doctor (Doctor of the English)[14] | 672 | 735 | 1899 | Priest, monk, OSB | Ecclesiastical History of the English People, The Reckoning of Time, Liber epigrammatum, Paenitentiale Bedae |

| 24. | Ephrem*[15] | 306 | 373 | 1920 | Deacon | Commentary on the Diatessaron, Prayer of Saint Ephrem, Hymns Against Heresies | |

| 25. | Peter Canisius | 1521 | 1597 | 1925 | Priest, SJ | A Summary of Christian Teachings | |

| 26. | John of the Cross | Doctor mysticus (Mystical Doctor) | 1542 | 1591 | 1926 | Priest, mystic, OCD (Reformer) | Spiritual Canticle, Dark Night of the Soul, Ascent of Mount Carmel |

| 27. | Robert Bellarmine | 1542 | 1621 | 1931 | Archbishop of Capua, Cardinal, Theologian, SJ | Disputationes de Controversiis | |

| 28. | Albertus Magnus[16] | Doctor universalis (Universal Doctor) | 1193 | 1280 | 1931 | Bishop of Regensburg, Theologian, OP | On Cleaving to God, On Fate |

| 29. | Anthony of Padua | Doctor evangelicus (Evangelical Doctor) | 1195 | 1231 | 1946 | Priest, OFM | Sermons for Feast Days |

| 30. | Lawrence of Brindisi | Doctor apostolicus (Apostolic Doctor) | 1559 | 1619 | 1959 | Priest, Diplomat, OFMCap | Mariale |

| 31. | Teresa of Ávila[17] | Doctor orationis (Doctor of Prayer) | 1515 | 1582 | 1970 | Mystic, OCD (Reformer) | La Vida de la Santa Madre Teresa de Jesús, The Way of Perfection, The Interior Castle |

| 32. | Catherine of Siena | 1347 | 1380 | 1970 | Mystic, TOSD | The Dialogue of Divine Providence | |

| 33. | Thérèse of Lisieux | Doctor amoris (Doctor of love); Doctor synthesis (Doctor of synthesis)[18] | 1873 | 1897 | 1997 | OCD | The Story of a Soul, Letters of Saint Therese |

| 34. | John of Ávila | 1500 | 1569 | 2012 | Priest, Mystic | Audi, filia; Spiritual Letters | |

| 35. | Hildegard of Bingen | 1098 | 1179 | 2012 | Visionary, theologian, polymath, composer, abbess OSB, physician, philosopher | Scivias, Liber vitae meritorum, Liber divinorum operum, Ordo virtutum, | |

| 36. | Gregory of Narek[19] | 951 | 1003 | 2015 | Monk, poet, mystical philosopher, theologian | Book of Lamentations | |

| 37. | Irenaeus of Lyon*[20] | Doctor unitatis (Doctor of Unity)[21] | 130 | 202 | 2022 | Bishop, theologian, Martyr | Proof of the Apostolic Preaching, Against Heresies |

Proposed Doctors

In October 2018, on the occasion of the canonization of Oscar Romero, martyred Archbishop of San Salvador, José Luis Escobar Alas, the current Archbishop of San Salvador, petitioned Pope Francis to name Romero a Doctor of the Church.[22]

In October 2019, the Polish Catholic Bishops Conference formally petitioned Pope Francis to consider making Pope John Paul II a Doctor of the Church in an official proclamation, in recognition of his contributions to theology, philosophy, and Catholic literature, as well as the formal documents of his papacy.[23]

In January 2023, Cardinal Angelo Bagnasco proposed that Pope Benedict XVI be declared a doctor of the Church “as soon as possible”, in view of his theological intelligence and contribution to the formation of current doctrine of the Catholic Church, such as the new catechism.[24][25] In January 2024, Archbishop Georg Gänswein also spoke in favor of the pontiff’s canonization and his elevation to the status of doctor of the church.[26]

In November 2023, the USCCB voted to support a petition by the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales for the Vatican to name John Henry Newman a Doctor of the Church.[27] The epithet Doctor amicitiae (Doctor of Friendship) has been suggested for St. John Henry Newman.[28]

Other recognized Doctors

In addition, parts of the Catholic Church have recognised other individuals with this title. In Spain, Fulgentius of Cartagena,[29] Ildephonsus of Toledo[30] and Leander of Seville[2] have been recognized with this title. In 2007 Pope Benedict XVI, in his encyclical Spe Salvi, called Maximus the Confessor “the great Greek Doctor of the Church”,[31] though the Congregation for the Causes of Saints considers this declaration an informal one.[32]

Scholastic epithets

Main article: Scholastic accolades

Though not named Doctors of the Church or even canonized, many of the more celebrated doctors of theology and law of the Middle Ages were given an epithet which expressed the nature of their expertise. Among these are Bl. John Duns Scotus, Doctor subtilis (“subtle doctor”); Alexander of Hales, Doctor irrefragabilis (“unanswerable doctor”); Roger Bacon, Doctor mirabilis (“wondrous doctor”); William of Ockham, Doctor singularis et invincibilis (“valuable and invincible doctor”); Jean Gerson, Doctor christianissimus (“most Christian doctor”); and Francisco Suárez, Doctor eximius (“exceptional doctor”).[33]