A.D. 1095 to 1270

History of the Crusades

The Crusades are often used as a classic example of the evil that organized religion can do. Your average man on the street would agree that the Crusades were an insidious, cynical, and unprovoked attack by religious zealots against a peaceful, prosperous, and sophisticated Muslim world.

It was not always so. During the Middle Ages you could not find a Christian in Europe who did not believe that the Crusades were an act of highest good. It was in the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century that the current view of the Crusades was born.

After the Second World War, however, opinion turned decisively against the Crusades. In the wake of Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin, historians found war of ideology—any ideology —distasteful. This sentiment was summed up by Sir Steven Runciman in his three-volume work, A History of the Crusades (1951-54). For Runciman, the Crusades were morally repugnant acts of intolerance in the name of God. The medieval men who took the cross and marched to the Middle East were either cynically evil, rapaciously greedy, or naively gullible. This beautifully written history soon became the standard. Almost single-handedly Runciman managed to define the modern popular view of the Crusades.[1]

Background[2]

In this study, it is important that we understand what events led up to the Crusades. Since the legalization of Christianity in A.D. 313 under the Roman Emperor, Constantine, European Christians began pilgrimages to Palestine to visit the holy sites associated with the life of Jesus. Travel in this era was difficult, time-consuming, expensive and dangerous.

Christians also took trips to Syria, Palestine and Egypt to live ascetic lives, especially in the 3rd century as Christian monasticism flourished. What was great for the pilgrims and ascetics was that their journey took them through Christian lands. This was no longer the case once Islam came onto the scene in A.D. 612. As Islam grew, Muhammad began conquering pagan, Jewish and Christian tribes. He seized control of his native Mecca as well as all of Arabia. He died in A.D. 632.

After Muhammad’s death, his successors continued and aggressive expansion of Islam. In less than a century they seized control of Syria, Palestine and North Africa. In time, even Europe itself was threatened. Muslims seized control of southern Spain, invaded France and we’re threatening to invade Rome itself when their advances was halted by their defeat at the Battle of Poitiers in A.D. 732 by Charles Martel.

The Muslims then turned their attention to conquering Persia (modern day Iraq), Afghanistan, Pakistan and parts of India within 2 centuries. Later, they also advanced against Christian nations, conquering the Byzantine Empire in A.D. 1453. The Crusades occurred in the middle of this struggle.

The Muslims had control of Palestine, but gave Christians some concessions to live there and to visit the holy sites. In 1009 the Fatimite caliph of Egypt ordered the destruction of the Holy Sepulcher– The tomb of Christ in Jerusalem–which was a principal focus of Christian pilgrimages. It was later rebuilt.

The number of Christians making pilgrimages increased due to the difficulty and thus a greater act of piety. In the 11th century, thousands of Christians made these pilgrimages and often travelled with armed Christian escorts that protected the pilgrims.

The Seljuq Turks took Jerusalem in A.D. 1070 and began threatening the Byzantine Empire. In 1071, the Seljuqs captured the Byzantine emperor Romanus IV Diogenes and his successor, Michael VII Ducas, asked Pope Gregory VII for help. The Pope did not help at this time because of the Investiture Controversy, where the emperor, Henry IV, began to install bishops against the Church’s will.

The Seljuqs expanded their conquest in A.D. 1084 by capturing Antioch and the city of Nicaea in 1092. By the 1090’s many of the major sees were in the hands of the Muslims and now the city of Constantinople was in danger of fallings. Emperor Alexius I Comnenus, appealed for help from Pope Urban II.

The First Crusade (1095-1101)

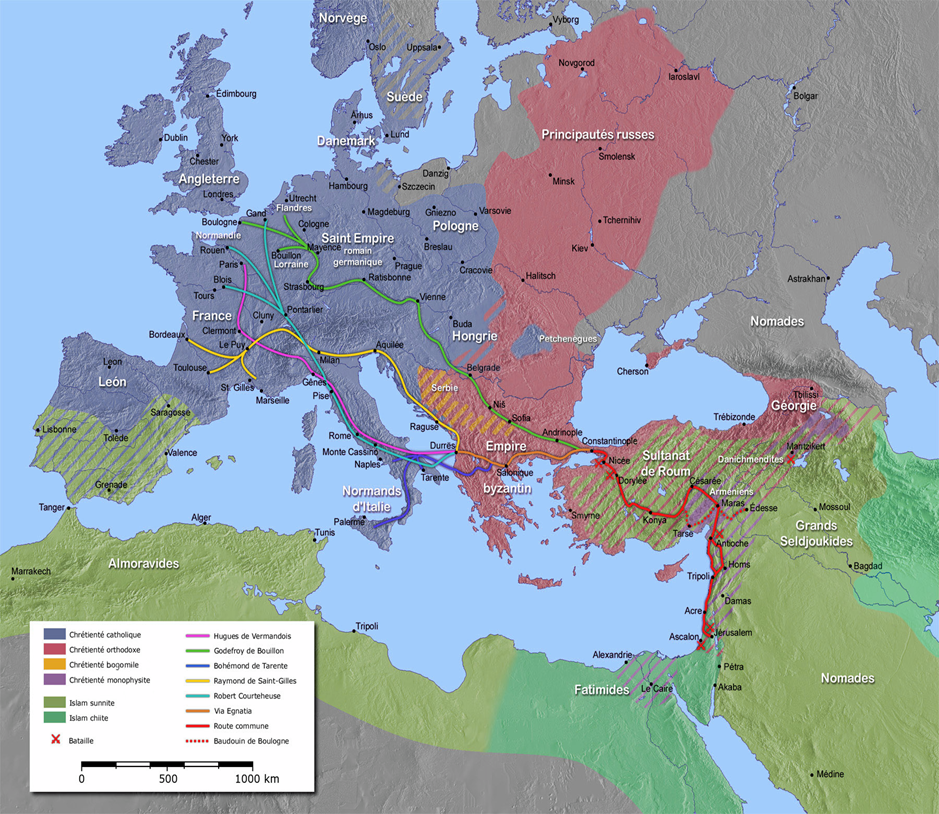

Pope Urban II was able to respond to the plea for help. In November of 1095, he convened the Council of Clermont in France to discuss the plight of the Eastern Christians. The planned departure was August 15, 1096. They discussed defending Christendom against the Muslim advances, assisting the Eastern Christians, and reclaiming the Holy Sepulchre. The Pope emphasized the need for penance and spiritual motives in undertaking the campaign.

He offered a plenary indulgence for those vowing to undertake it in this spirit and the response was extremely enthusiastic, with attendees crying Deus vult!—”God wills it!” It was also decided that those undertaking the campaign would wear a red cross, called a “Crux” in Latin, thus leading to the name “crusade.”

Preparations began across Europe, but were not always well-organized, nor did they always live up to the spiritual mandate of the pope. Some were so ill-equipped that as they journeyed that they turned to looting to find sustenance. Some never made it as far as Constantinople.

Others participated in the unauthorized and disorganized “Peasants’ Crusade.” This band of unskilled fighters was led by Peter the Hermit. These “crusaders” marched towards Jerusalem, but quickly found themselves engaged in destroying Jewish communities and killing Jews. The Turks quickly annihilated this poorly organized group.

In June 1097 Nicaea was surrendered to the Byzantines accompanying the crusaders, and the next month the crusaders and Byzantines won a major victory against the Turks when they were attacked at Dorylaeum (near Nicaea). Further progress was hard going and Alexius became dispirited. He had promised to assist in the siege of Antioch, but when the Emperor balked at this, the crusaders considered themselves relieved of any obligation to turn the city over to him since he would not help fight for it. Thus when it was taken in June 1099, it passed into Norman hands.

In July 1099, the Fatimid Muslims of Egypt retook Jerusalem from the Seljuqs, so it was in non-Turkish hands when the crusaders mounted their assault. For a month the crusader force, which had been reduced to about half its original size, had encamped around Jerusalem waiting for supplies. The crusaders soon received supplies from the port of Jaffa and made their move.

On July 8th they fasted and processed barefoot around the city to the Mount of Olives, then on the 13th they besieged the walls. On the 15th, some men got over the wall and opened one of the city gates, allowing the main force inside. In the Tower of David, the Fatimid governor surrendered and was escorted from the city. In the al-Aqsa Mosque by the Temple Mount, Tancred promised protection to the city’s Muslim and Jewish inhabitants, but despite his efforts a general slaughter ensued.

Many of the coastal cities remained under Muslim control despite the crusader’s victory. Most crusaders departed for home since the objectives of the crusade had been achieved and their vows had been fulfilled.

In the wake of the First Crusade there developed four Christian states from the territory the crusaders had recovered: the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Principality of Antioch, the Countship of Edessa, and the Countship of Tripoli. Relations between the states, the Byzantine Empire, and the surrounding Muslim domains were often complex.

To defend the new states, a new kind of fighting force developed—the religious orders of knighthood, such as the Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem and the Templars. These were groups of knights who took religious vows and accepted a religious rule.

For a time the crusader states flourished. Over time they expanded to include coastal cities originally left un-reclaimed. However, the states remained vulnerable, and in A.D. 1144 the northern state of Edessa was captured by Muslim forces.

The Second Crusade (1146-48)

In response to the fall of Edessa, Pope Eugenius III called a new crusade. St. Bernard of Clairvaux was key in preaching in France and Germany to promote the 2nd Crusade. He also preached that the Jews were not to be persecuted. The King of France, Louis VII, promptly responded, but the German Emperor, Conrad III, took more persuading. The Byzantine Emperor, Manuel Comnenus, was in favor of the crusade, but he did not contribute troops to the cause.

The Second Crusade had the largest crusader army to date, but met with less enthusiasm than the First, mostly because Jerusalem was still in Christian hands. The Crusade struggled to progress because of competing interests between the Germans and the French. The journey to the Holy Land was difficult and hardships took their toll. Unable to reach Edessa, the crusaders concentrated on taking Damascus, but inner turmoil and treachery forced them to retreat.

The failure of the Second Crusade was severely discouraging, and many in Europe became convinced that the Byzantine Empire was an obstacle to the success of the venture. The failure also boosted the morale of Muslim forces, since they had suffered a great defeat in the First Crusade.

The position of the crusader states continued to weaken and in a few years they became virtually encircled by a consolidated Muslim power following the collapse of the Fatimid caliphate in Egypt.

For a time there was a truce with the Muslim commander, Saladin, but the truce was broken in 1187 when a Muslim caravan was attacked. As a result, Saladin responded by declaring a jihad.

The Latin forces suffered a humiliating defeat at the Horns of Hattin (Northern Israel) and Saladin then proceeded to take Tiberias and the port city of Acre before turning to Jerusalem, which fell on October 2, 1187. By 1189, few cities in the crusader states were left in Christian hands.

The Third Crusade (1188-92)

Following the fall of Jerusalem, Pope Gregory VIII called for the Third Crusade. It was unfortunately beset by the untimely deaths of the kings who first stepped forward to lead it.

The first king to respond, William II of Sicily, sent a fleet East but died in late 1189. Henry II of England agreed to participate, but also died in that year. The German Emperor, Frederick Barbarossa, having reconciled with the Church, also participated and led a large army that defeated a Seljuq force in May 1190, but the next month the elderly Emperor drowned trying to cross a river on horseback. As a result, his army returned home before reaching the Holy Land.

The two kings who finally led the crusade were Richard I (“the Lion-Hearted”) of England, Henry II’s son and successor, and Philip II Augustus of France.

On his way to the Holy Land, Richard I stopped on the island of Cyprus, where he was attacked by the Byzantine prince Isaac Comnenus. Richard defeated the prince and took control of the island before sailing for the port city of Acre.

Reinforced by the arriving crusaders, Acre held out and the Muslim forces finally surrendered. Philip II then considered his crusader vow fulfilled and departed for France.

Saladin agreed to an exchange of prisoners and the return of the relic of the True Cross. This arrangement fell apart when Richard disputed the selection of returning prisoners and eventually ordered the execution of the Muslim captives and their families.

Richard was desirous of pressing forward to Jerusalem and was able to reclaim several cities, including Jaffa. He was ultimately unable to reach the Holy City, because he could not establish supply lines and finally gave up. In late 1192, Richard and Saladin signed a five-year peace treaty that allowed Christian pilgrims to have continued access to the holy places. The Christian holdings in the Holy Land now were reduced to a small kingdom composed largely of port cities.

The Fourth Crusade (1201-1204)

The Fourth Crusade was an unmitigated disaster. It was an appalling fiasco that did nothing but cause internal damage to Christendom.

In 1198, Pope Innocent III proposed a new crusade. As usual, the French responded to the call. The new target was to be Egypt, a formerly Christian land that was now a Muslim stronghold.

The crusaders turned to the Venetians for transportation, but when they proved to have insufficient funds to pay, the Venetians suggested that they instead attack and capture Zara, a Hungarian and Christian city. Many objected strenuously—including the Pope, but his orders were ignored and the crusaders took Zara at the bidding of the Venetians.

Matters went from bad to worse when Alexius, the son of deposed Byzantine Emperor Isaac Angelus, sought the aid of the crusaders in recovering his father’s throne. Promising rewards, Alexius convinced them to try. The Pope’s letter forbidding the expedition arrived too late, and the crusaders attacked Constantinople, reinstalled Isaac as Emperor, and proclaimed his son co-Emperor.

Innocent III reprimanded the leaders and ordered them to proceed to the Holy Land, but only a few did so. Most awaited the rewards that Alexius had promised, which, by the way, never happened.

Displeased by these promises to the Latin forces, the Byzantines promptly assassinated Alexius, following which the Venetians and the crusaders took control of the city and the empire. Constantinople fell to them on April 13, 1204, initiating a three-day chaos of looting and murder. Afterwards, a Latin Emperor of Constantinople was elected by a council composed of Venetians and crusaders. The Byzantine government relocated to Nicaea, where it remained, ruling only a portion of its previous territory until 1261, when Constantinople was reconquered by Michael VIII.

This crusade failed to even engage the Muslim forces occupying the Holy Land and it further divided Eastern and Western Christendom. It also permanently damaged the Byzantine empire, which had served as a buffer between Muslim aggression and the Christian heartland.

In the years following the Fourth Crusade, there were a number of minor crusades—wars whose participants took a vow—against heretics and others. Of particular interest was the so-called “Children’s Crusade” (1212), in which thousands of children set forth to conquer the Muslims forces with love instead of arms. A visionary child in France led one arm of the movement, while a German child led the other. Many children made it to Italy. However, the movement never reached the Holy Land, and the overwhelming majority of the children either died of hunger or exhaustion or were sold by unscrupulous Italians into Muslim slavery. The movement did, however, serve to incite feeling for the coming Fifth Crusade.

The Fifth Crusade (1217-1221)

The final crusade in which the Church played a major role was the fifth. It was called for by the pope of the previous crusade, Innocent III, as well as by the 12th ecumenical council, Lateran IV. As in the prior effort, the target was not Palestine itself, but Egypt, the basis of Muslim power, which the crusaders hoped to use as a bargaining piece to secure the release of Jerusalem.

Unlike the prior effort, which spun out of control in the hands of laymen, this effort was placed under the authority of a particularly forceful papal legate, Cardinal Pelagius. He had a regal disposition and regularly meddled in military decisions.

The effort met with initial success, and alarmed Muslim forces offered generous terms of peace, including the surrender of Jerusalem. However, the crusaders, spurred by Cardinal Pelagius, refused these. A military blunder cost the crusaders Damietta, which they had captured in the early stages of the campaign. In 1221, the Christian forces accepted a truce far less favorable than what had been offered initially. Many blamed Pelagius. Others blamed the pope. Some blamed the German emperor, Frederick II, who failed to show up for this crusade but who was to play a prominent role in the next.

The Sixth Crusade (1228-29)

Innocent III had granted Frederick II several delays in the fulfillment of his crusade vow so that he could take care of matters in Germany. Innocent’s successor, Gregory IX, tired of Frederick’s dallying and insisted that he fulfill his vow. When the emperor stalled again, citing illness, the pope had had enough and excommunicated him. When Frederick finally embarked, he was crusading as an excommunicate.

This odd situation led to an odd crusade. In part because of Frederick’s excommunication, few were willing to support him and he was unable to mount a major military campaign. As a result, he turned to diplomacy and, taking advantage of divisions among Muslims, worked out a treaty in 1229 with Sultan al-Kamil of Egypt, according to the terms of which Jerusalem (less the Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa Mosque), Bethlehem, Nazareth, and additional territory were returned to the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Frederick II, still excommunicated, was then crowned king of Jerusalem in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in a non-religious ceremony (since Jerusalem had been placed under interdict as a result of Frederick’s presence). The following year he was reconciled to the Church. He was unable, however, to successfully rule the Kingdom of Jerusalem from a distance, for the local barons refused to cooperate with his representatives.

The years 1239 and 1241 saw two minor crusades, respectively by Count Thibaud IV of Champagne and Roger of Cornwall. These two efforts, in Syria and against Ascalon, were unsuccessful and minor enough that they are not numbered among the standard eight crusades.

The Seventh Crusade (1249-52)

The initiative for the penultimate crusade was taken by Louis IX of France. Again, the strategy was pursued of attacking Egypt to gain concessions in Palestine. The crusaders quickly captured Damietta again but had to pay a heavy price in taking Cairo. A Muslim counter-attack succeeded in taking Louis prisoner. He was later released after agreeing to turn over Damietta and to pay a ransom. Afterward, he remained in the East for several years to negotiate the release of prisoners and fortify the Christian foothold in the region.

The Eighth Crusade (1270)

The last of the eight crusades was also led by Louis IX. In the ensuing years, changes in the Muslim world led to a renewed series of attacks on Christian territory in the Holy Land. The locals made appeals to the West for military aid, but few Europeans were interested in mounting a major campaign. One who was willing to again take the crusader’s cross was Louis IX, who wished to make good his previous failure. However, the campaign he now mounted achieved less for the Kingdom of Jerusalem than had the former.

It is not certain why, but Tunis in North Africa was picked for an initial target. Once there, plague claimed the lives of many, including the pious Louis. His brother, Charles of Anjou, arrived with Sicilian ships and was able to evacuate the remainder of the army.

Though this was the last of the eight enumerated crusades, it was not the last military expedition to be considered a crusade. Campaigns continued to be waged, against a variety of targets, not just Muslim ones, by crusaders—men who had taken a vow to undertake the fight.

For their part, the Christians of Palestine were left without further aid. Despite continuing losses, the Kingdom of Jerusalem managed to hang on in some form until 1291, when it finally ceased to exist, thus erasing the Crusader Kingdom from the map. Christians, though, continued to live in the area even after its fall.

Summary

Many today in the West view the Crusades as acts of unjustified aggression toward the peaceful inhabitants of the East and the Holy Land. A study of history shows this view as unsustainable.

This may be seen clearly, for example, by transposing the roles of the forces. If the Crusades had occurred in the middle of a multi-century campaign in which Christians consumed half of what historically had been Muslim territory, few would regard Muslims as completely unjustified in striking back, in an attempt to reclaim lands lost to Christians, especially if these lands contained many of their religious faithful.

Few would expect Muslims to sit idly by if Christians seized control of and denied Muslims access to the Kaaba in Mecca and the Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem. It would be fully expected that Muslims would retaliate and seek to reclaim control of or access to their holy sites.

Common sense makes it difficult not to see among the chief lessons of the Crusades “Don’t conquer half of another group’s civilization without expecting reprisals” and “Don’t touch a people’s holy sites without expecting retaliation.”

Christians today certainly should deplore evil acts committed during the Crusades, such as the massacres of innocent Muslims and Jews that periodically occurred, as well as the entire debacle of the Fourth Crusade. However, the enterprise of the Crusades themselves had two important goals at its core:

- The defense of Christian civilization against outside aggression (making the Crusades, as a whole, wars of self-defense) and

- Securing access to the holy sites that commemorate to the most important events in Christian history.

======++++++++=======

Additional History

In 1480, Sultan Mehmed II captured Otranto as a beachhead for his invasion of Italy. Rome was evacuated. Yet the sultan died shortly thereafter, and his plan died with him. In 1529, Suleiman the Magnificent laid siege to Vienna. If not for a run of freak rainstorms that delayed his progress and forced him to leave behind much of his artillery, it is virtually certain that the Turks would have taken the city. Germany, then, would have been at their mercy.

Yet, even while these were taking place, something else unprecedented was beginning in Europe. The Renaissance, born from a strange mixture of Roman values, medieval piety, and a unique respect for commerce and entrepreneurialism, had led to other movements like humanism, the Scientific Revolution, and the Age of Exploration. Even while fighting for its life, Europe was preparing to expand on a global scale. The Protestant Reformation, which rejected the papacy, made Crusades unthinkable for many Europeans, thus leaving the fighting to the Catholics.

In 1571, a Holy League, which was itself a Crusade, defeated the Ottoman fleet at Lepanto (Greece). Yet military victories like that remained rare, but the Muslim threat was neutralized economically. As Europe grew in wealth and power, the once awesome and sophisticated Turks began to seem backward and no longer worth a Crusade.

From the safe distance of many centuries, it is easy enough to scowl in disgust at the Crusades. Whether we admire the Crusaders or not, it is a fact that the world we know today would not exist without their efforts. The ancient faith of Christianity, with its respect for women and antipathy toward slavery, not only survived but flourished. Without the Crusades, Christianity might well have followed Zoroastrianism, another of Islam’s rivals, into extinction.[3]

“Come Holy Spirit” Prayer

Come Holy Spirit, fill the hearts of your faithful and kindle in them the fire of your love.

Send forth your Spirit, and they shall be created.

And You shall renew the face of the earth.

Let us pray.

O, God, who by the light of the Holy Spirit, did instruct the hearts of the faithful, grant that by the same Holy Spirit we may be truly wise and ever enjoy His consolations. Through Christ Our Lord. Amen.

[1] Catholic Dossier article by Thomas F. Madden, Crusade Myths. Vol. 8, No. 1, Jan-Feb 2002

[2] Borrowed heavily from Catholic Dossier article by James Akins, The Crusades 101. Vol. 8, No. 1, Jan-Feb 2002

[3] Borrowed heavily from Catholic Dossier article by James Akins, The Crusades 101. Vol. 8, No. 1, Jan-Feb 2002